from sojo.net - 2016

'God Is Not Finished With This World' by Christine A. Di Pasquale

Sojourners contributor Christine A. Scheller caught up with Bishop Curry during a recent trip to New Jersey for a diocesan convention. There, they chatted what’s ahead for the church, what it means to love our neighbor, and what Christians should keep in mind while voting in this year’s elections.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Christine A. Scheller, contributor, Sojourners: Do you attend all diocesan conventions? Presiding Bishop Curry: Part of the responsibility of a presiding bishop is to visit every diocese in the Episcopal Church in the course of nine years. And so, sometimes I’ll go at the time of a convention. Sometimes a diocese will want you to come for a different occasion and do something there. Sometimes when a bishop is being consecrated you go and spend some time there.

Scheller: I’m a member of a small, wealthy, white Episcopal congregation at the Jersey Shore. How do churches like mine support work in cities like Camden, N.J. [one of America’s poorest cities, and a member of the Diocese of New Jersey] without being paternalistic? Curry: Everything is built on relationships — real relationships where people actually get to know each other. And then shared ministry and programmatic kinds of things emerge out of that relationship. When I was a diocesan bishop trying to encourage congregations to develop relationships with other congregations of a different ethnicity or tradition, I encouraged them to worship together, or eat together, get to know each other, eventually finding ways for people to share their stories about their faith. That avoids the paternalistic or maternalistic model because when you build on relationships, the stories of people’s lives, everybody’s story is equal. And that sharing and listening creates incredible space and bonds between people that it’s hard to create otherwise.

Scheller: With a theology and perhaps politics that is more progressive, one would think the Episcopal Church would be more ethnically and racially diverse than it is. Is there a way to help people who are privileged in various ways to see what people who have less resources can offer to them? Curry: There are going to be uniquenesses to every relationship, and some commonalities. One, have some shared life together, and shared life that really is equally shared, equally given and equally received — for example, the dioceses that have companion relationships with dioceses in the developing world. And two, take money out of the equation and ask, What gifts do we bring? Then we’re starting to get to a level of real human gifts.

It may be that part of what has to happen is that each congregation has to have an internal conversation and orientation in getting to know the other congregation, because we all come to the table with some presuppositions and some assumptions about each other. If there’s a common commitment to really getting to know each other and giving and receiving our gifts that moves us beyond, “I’m in charge, you’re not. I’m privileged, you’re not,” it’s in that space that we discover something that can make stuff happen.

Scheller: It sounds like you could be talking about some of the larger challenges in the Anglican communion. Do you have hope for relationships in the wider communion? Curry: I have a little bit more than hope. I actually have a belief that God is not finished with this world, and God is not finished with the human family yet, and that applies as much to the Anglican communion or the family of nations as to the human community. I refuse to believe that we cannot learn to live together. I believe that that’s what Jesus came to teach us and to show us how to do.

And frankly, he has shown us the path to be able to live together across differences, live together in ways that have integrity, that are deeply grounded in love and not grounded in my opinion. When we get to that level, then it is possible for people to hold very different perspectives and yet to realize that it’s the relationship with my brother or my sister that really matters. I think that’s going to be true with us in the Anglican communion. It’s true with us in the United Nations, it’s true in the global community, and it’s true in relationships between congregations and on the streets of the cities.

Scheller: What other hopes do you have for the communion? Curry: People in the NGO world will often tell you that the most effective human service delivery systems are actually church systems around the world. The Anglican Communion, of which the Episcopal Church is a part, is one of the three largest [church systems], and so my hope and prayer is that the Anglican communion will continue to be a vehicle of delivery of human services that not only responds to emergencies, but that is involved in much more long term human development and in the eradication of poverty.

The church’s

Sustainable Development Goals are about abolishing poverty on the face of this planet by the year 2030, and we actually have the capacity to do it if we have the will. The Anglican Communion can play an important part in that. That’s one of my greatest hopes.

A second one that would be similar is that, while I know we have clearly different positions and perspectives on the question of who may be married, I hope that we in Episcopal Church will be able to bear witness to the call of Jesus to help the church to truly become what Jesus said — a house of prayer for all people. And that we will be able to bear witness to that conviction in the communion, and to help us as a communion discover how we may be called to live that out for everybody — gay, straight, black, white, rich, poor, male, female, everybody. I’m not prescribing exactly what that looks like, but living by that biblical principle.

I’m just quoting Jesus. He said that on Palm Sunday. He was quoting the prophets when he said it, so this is an old understanding and tradition. Living by that principle could be transformative, and it’s my hope and prayer that we will live deeply into those words of Jesus. There can be room for us all as the baptized people of God. Hopefully then, we can have a voice for the whole world that there’s room for all of us on the planet as equal children of God.

Scheller: You have prioritized evangelism and reconciliation in your ministry as presiding bishop. In a community like Camden, N.J., what does that look like? Do you have any ideas germinating from your tour of the city? Curry: It takes many forms. But both evangelism and reconciliation are actually different sides of the same coin, because I think the core mission or purpose of the church is to help to unite people in a relationship with God through Christ, and with each other as children of God. Some of the work that draws us closer to God also draws us closer to each other. It can take many forms. We just left a place that was once a church building and is now a place where children and young people build boats not simply to learn a craft, but to learn that they can be part of the creative process. That creative process is something that they can participate in, that can draw them closer to the ultimate Creator himself.

Scheller: We saw that creativity twice today, especially here at the Urban Boatworks and at Hopeworks. Curry: There was a stunning picture in Hopeworks of Jesus and I think it said “Real Hope.” Our real hope is in God, the relationship with God, and the relationship with each other that is reconciled and right and whole. Reconciliation isn’t just about singing “Kumbaya,” it’s about restoring things to the way they were meant to be. Reconciliation involves doing what is just and what is right, and reordering the way we live together so that none has need, so that children do not starve, so that every child here in Camden has an opportunity to have an excellent education so that they can become all that they can be, that no child should be deprived in this great country.

The truth is none should be deprived on the face of the earth, but we happen to live here. And we who are Christian are people who are fundamentally committed to the love of God, and love of neighbor. This is not a Valentine’s Day card. Dietrich Bonhoeffer once said that love in the Bible is cruciform. It’s the shape of a cross. It is Jesus giving his own life, not for himself, but for the good and the welfare of others. That’s what love is. It’s not a sentiment. It’s a deep-hearted commitment to seek the well-being of the other, before one’s own unenlightened self-interest. That kind of love changes societies and changes lives.

Scheller: How should Christians be thinking about living out their hope and their faith in the political context of this interesting presidential election? Curry: I really believe that the fundamental principle on which Christians stand as followers of Jesus Christ is what Jesus taught and embodied in his life: love God, and love your neighbor. “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength, and love your neighbor as yourself.” In Matthew’s version Jesus says, “On these two hang all the law and the prophets,” which is basically saying that everything in the religious faith — everything — has to do with love of God and love of neighbor. It may say it in a different way or form, or apply it differently, but that is the bottom line.

If we who are Christians participate in the political process and in the public discourse as we are called to do — the New Testament tells us that we are to participate in the life of the polis, in the life of our society — the principle on which Christians must vote is the principle, Does this look like love of neighbor? If it does, we do it; if it doesn’t, we don’t.

We evaluate candidates based on that. We evaluate public policy based on that. And that has nothing to do with whether you’re a Republican or a Democrat, liberal or conservative. It has to do with if you say you’re a follower of Jesus, then you enter the public sphere based on the principle of love which is seeking the good and the welfare of the “other.” That’s a game-changer.

And so, when you’re involved in votes that have to do with public education or that have to do with anything, always ask the question, “Is this something that you would want someone to do to you, or to those you love?”

Scheller: Until you got to that last line, I would have said people define love differently. Some might say it’s a loving thing to do to make people responsible for themselves. Curry: That’s legitimate. There is a case to be made for that. There is going to be variety in the practical application. But I really do believe that we have a different quality of politics if we have people who actually are doing their politics by the Golden Rule. It doesn’t mean that everybody is going to agree, but you cannot say you’re voting as a Christian if you don’t apply the Golden Rule. You can’t. Jesus said that. He taught us that. It’s in the Sermon on the Mount. You can’t say you’re functioning as a Christian in the political sphere if you’re not functioning on the principle of love. You can say you want to function another way. That’s fine. It’s a free country. Go ahead. But you can’t say you’re a follower of Jesus of Nazareth and not function on the law of love, the Golden Rule, and those kinds of teachings.

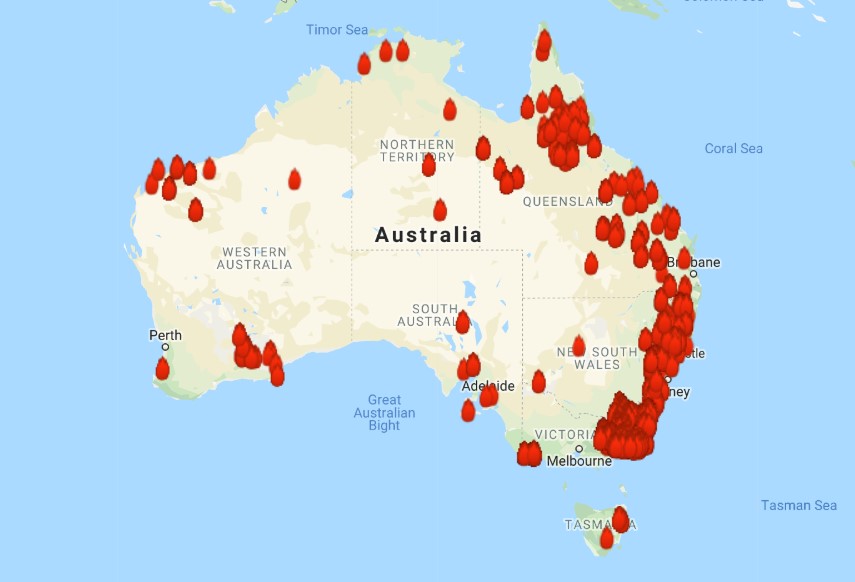

New South Wales

New South Wales